January, 2024:

This essay uses extracts and paragraphs from a University essay I recently completed, I felt that the topic was transferable so I have based this post on it.

I’ve previously written about Boards of Canada and my love for Intelligent Dance Music [henceforth: IDM]. I continually find myself going back and listening to The Campfire Headphase and Music Has The Right To Children when I’m studying, with Geogaddi and Tomorrow’s Harvest being the soundtrack to my runs and walks. The music has such an emotional quality, described by Journalist Richard Hector-Jones as having “a uniqueness, a ghostly sense of yearning, and a depth of emotion that sets them far outside the pack”.

My engagement with IDM epitomises the academic movement towards non-representational approaches in musical geographies, breaking away from the textual and musicological analysis of prior research praxis (pace Moss, 1992; 2011; Rhodes & Post, 2021) to investigate the “creative and evanescent qualities” of musical ‘performance’ in both production and consumption (Wood et al., 2007: 868; Whittaker, & Peters, 2021; Smith, 2000). This research was radically cultural, investigating the role of imagined phenomena [akin to Heidegger’s imagined intentionalities in his existential phenomenology] in creating relational and æffective experiences of pre-recorded music. As IDM has no lyrics, a minimal construction, and purely electronic musical instruments, I thought it would be the perfect genre for my own musical creation.

In my essay, I included my own definition of IDM given the heterogeneity of online sources which claim to produce a succinct explanation. For me, this was immense, as I got to marry my musical obsession with academic work. I’ll include this in its entirety, but if you can’t be bothered to read it, skip to the end for the music.

Towards a Definition of ‘Intelligent’ Dance Music:

Originating in the early 1990s, Intelligent Dance Music is a divisive term used to describe a broad range of Electronic Dance Music [EDM] sub-genres which preference a more ambient and minimalist construction (AllMusic, n.d.). Whether the term itself constitutes an independent genre is highly debated, with prominent artists such as Kid 606 stating that IDM is simply “a label invented by PR companies who need catchphrases” (ibid.). The term ‘intelligent’ stems from Warp Record’s 1992 compilation album ‘Artificial Intelligence’, encouraging listeners to take a more critical and ‘intellectual’ approach to electronic music by sitting down and listening, rather than actively dancing (Reynolds, 2013). Consequently, an individualised and relational place of consumer performance is created, associating the genre with “spatial and social rules of etiquette” akin to those exhibited at live concerts (Wood et al., 2007: 872; Smith, 1992).

However, categorising dance music as ‘intelligent’ consequently insinuates the presence of ‘stupid’ dance music. This elitist notion of labelling music as ‘intelligent’ has been extremely contentious, especially given that IDM and countless other EDM genres stylistically originated from Afro-American/Afro-Caribbean music such as Hip- Hop, Jungle and Dub (Reynolds, 2012; Alwakeel, 2009). In UK Drum & Bass [DnB], a fringe sub-genre predominantly created by white-British artists such as Marcus Intalex and Blame was termed Intelligent Drum & Bass [IDB] and included in the IDM charts (Reynolds, 2013). Despite largely being a marketing move to make DnB more appealing to “white middle-class hipsters” (Murphy & Loben, 2021: 181), issues of racism and classism embedded in the lexicon of the music industry continue to plague the term. Nevertheless, the expression continues to be used, with the music industry continuing to assert that ‘intelligent’ music is that which is consumed in a sedentary and attentive manner (Frere-Jones, 2014).

Stemming from the focus on active listening, IDM combines elements from both poles of the electronic music spectrum to create complex records designed to enhance introspection. Breakbeats, sound design and sound effects from “hard-edged dance music” sub-genres like Breakbeat, DnB/Jungle and Techno are combined with ephemeral synths, chord progressions and slow tempos commonly used in Ambient and Dub records (AllMusic, n.d.). Given the heterogeneity of IDM music, it is difficult to concisely find an established definition. For my project, I collated records from several IDM producers, including Boards Of Canada, Squarepusher, Aphex Twin, Marcus Intalex inter alios, to create my own explanation.

The defining characteristic of IDM is the general ambient or minimalist construction to the music, with Marcus Eoin stating that it is “[t]he spaces in between the music you’re supposed to listen to” (Hector-Jones, 1998). Consequently, the listener is free to use their own experiences and imagination to fill the empty sonic space; axiomatically inviting ‘audience’ participation and conscious dialogue (Wood et al., 2007). Nearly all songs are without lyrics in the traditional sense, although some feature voices/spoken word: such as the number station in Boards Of Canada’s ‘Aquarius’ or the female vocaliser in Aphex Twin’s ‘Xtal’. Moreover, numerous songs use soundscapes to convey inter-subjective notions of space/place, such as Boards Of Canada’s ‘Satellite Anthem Icarus’ using a generic beach soundscape. Not all songs include drums, with many artists preferencing acoustic tracks like Squarepusher’s ‘Tommib’. When drums are included, they use breakbeat patterns from jungle music which sample live ‘breaks’ into syncopated, repetitive rhythms. Further elements are also commonly seen across tracks, with IDM being synth-driven, using ‘pads’ sustaining long notes to create a sense of continuity. Pads, among other synths, contribute to IDM’s ethereal and highly technological sound as sounds are specifically designed to evoke certain emotional responses, similar to the techniques used in film scoring (Kirby, 2021) and ambient music production (DeNora, 2006). Additionally, individual instrument tracks are ‘soundstaged’, a term used to describe the process of panning to create the illusion of a live performance by having sounds play independently in each ear; evidenced in Boards Of Canada’s ‘Dayvan Cowboy’. Consequently, the sonic make-up of IDM provides a middle ground between the bass-driven, energetic dance music played during ‘raves’ and the downtempo music heard in chill-out rooms and after- parties (Reynolds, 2013).

As listening is a core component of ‘musicking’ generally (Smith, 1998), I was initially unsure as to why IDM music had such an emotional impact on myself. However, as IDM is “equally comfortable on the dancefloor as in the living room” (AllMusic, n.d.), a new liminal space of private consumption is formed, with electronic music production no longer bound the socio- spatial norms of either rave or downtempo environments (Smith, 1992; Alwakeel, 2009). In preparation for my project, I found that the combination of sedentary performative praxis and empty sonic space within the songs leaves abstract ‘space’ for me [the listener] to imagine and attribute my own meaning and/or location to songs upon each listen. Just as “physical space for music making…is, then, a potential“, so too is the abstract space within listeners’ imaginations (Wood et al., 2007: 869). This understanding localises musical performances into everyday, private live, demonstrating the importance of non-representational music methodologies outside of live concerts.

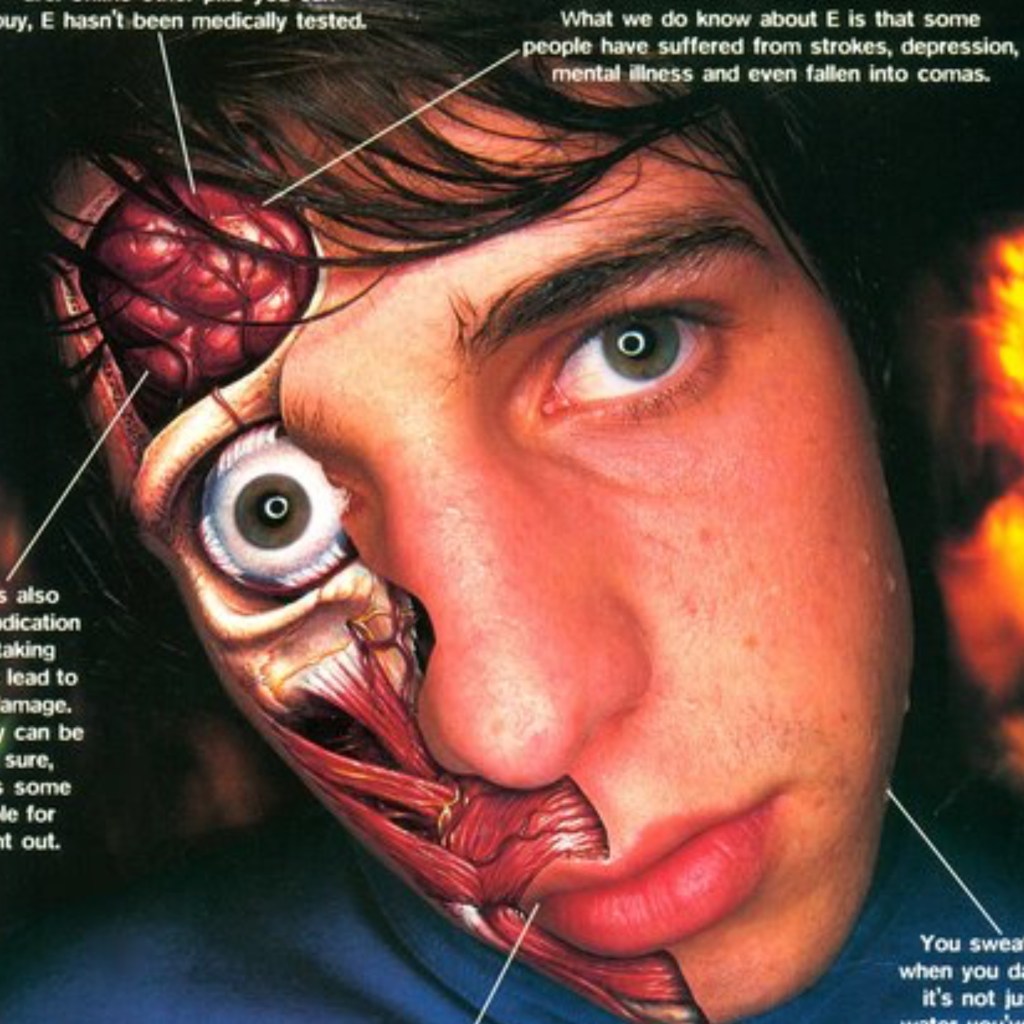

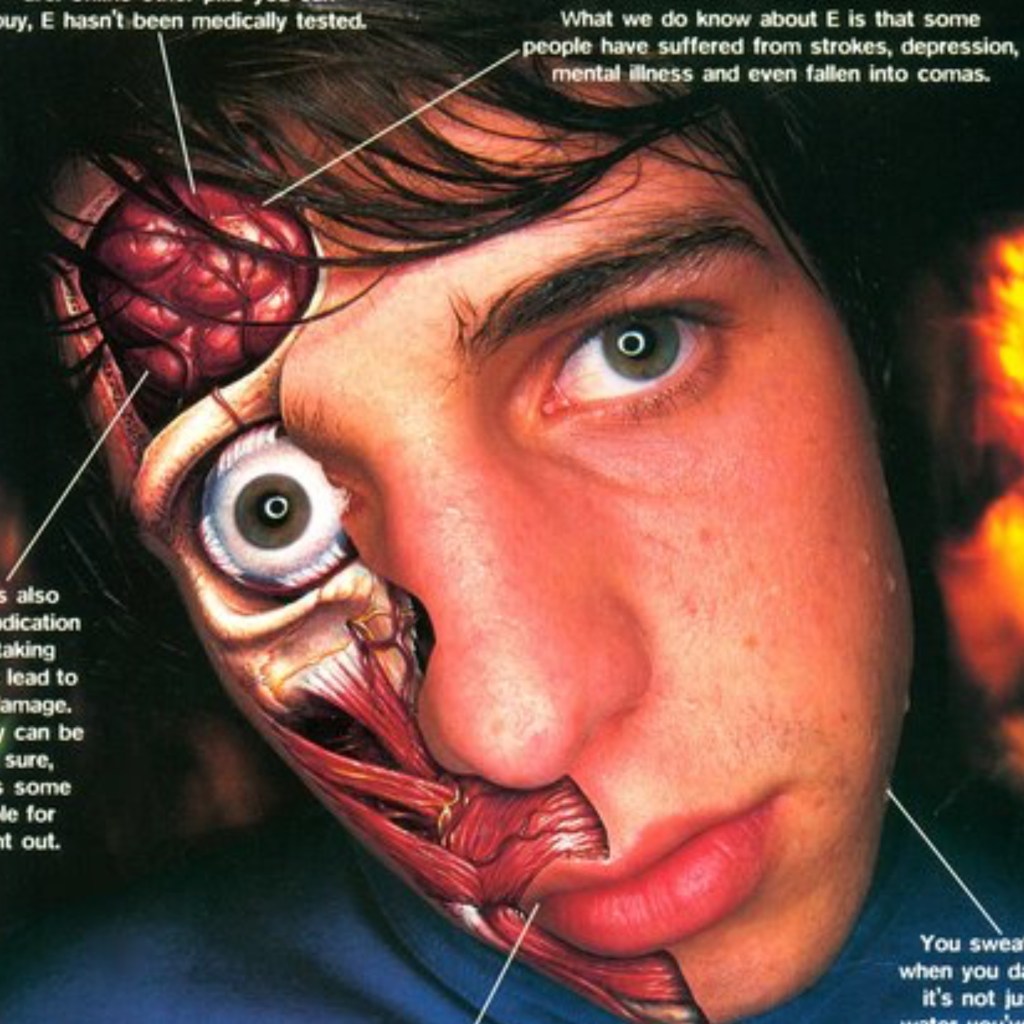

Moreover, to augment the sedentary experience, listeners often use dissociative and analgesic drugs such as ketamine and wear blackout eye masks to amplify the ethereal and emotive potentiality of the music. Of course, questions over the veracity of disassociation are highly subjective; although, liminal and phantasmagorical imagery can be seen in numerous album covers, such as Boards of Canada’s ‘Music Has The Right To Children’ or Aphex Twin’s ‘Come To Daddy’. Consequently, the interplay between disassociate consumption and liminal spatialities of production amplifies the affective experience of IDM. Whilst some albums encourage listeners to access an immediate utopia by creating the “fleeting presence of a life that momentarily forgets anxiety and isolation” (Anderson, 2016: 21), others access a range of negative emotions such as “paranoia” (Richardson, 2002), “disorientation” (Dack, 2021), or “wonder and dread” (Lynskey, 2013). Album artwork for ‘Come To Daddy’ by Aphex Twin (1997) [left] & ‘Music Has The Right To Children’ by Boards of Canada (1998) [right].

In addition to emotions, IDM has a long-standing history of representing spaces and places through specific sound design and soundscapes. Reviewing various albums by Boards Of Canada, Lynskey (2013) discusses how ‘Music Has The Right To Children’ and ‘The Campfire Headphase’ are “redolent of northern fields and forests”, while their later album ‘Tomorrows Harvest’ evokes the “American desert, specifically the secret landscape of atom bomb tests, peyote trips, religious sects and Area 51”. The specificity of spatial description elucidates the importance of non-representational and affective sonic phenomena in our understanding of space (Saldanha, 2005; Wood, 2005), with seemingly minor sonic details evoking vivid memories and/or conceptualisations of specific spaces.

So from this base, I created my three songs. Axiomatically, in my production process, I prescribed [representational] meaning to the songs, yet this essay was really trying to get at the individuality and relational nature of pre-recorded music. Consequently, discussions of performance in relation to music consumption are localised further into the everyday, additionally opening discussion into the de-/post-human/ANT geographies of performance and affect.

The three songs are included below, and I urge you to listen to them and find your own meaning. Listen to them during the day or night, inside or outside, tired or awake etc etc etc. I hope that upon each listen, you will notice something different in the song, yet your trans-subjective meaning prevails throughout. I am currently undergoing the process for these songs to be released on Spotify and Apple Music, I’ll chuck the links in when thats completed. They will be released as part of an EP called ‘Phenomenology’, with the album artwork included as the cover photo for this post.

• Blade

• Carlisle

• South

Leave a comment