“The supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging. Also: something characterized as likely to lead to such deterioration.”

Oxford Dictionary – 2024 Word of the Year

I never thought I’d be writing this sentence: the cultural impact of brain rot is poorly understood. The internet has always been a safehaven for niche internet fandoms, memes and communities. Masspersonal communication networks and social media sites have brought disperate populations together in ways that the cultral products associated with early Hertzian networks never achieved. Reymond Williams’ materialist perspective on the inherent materiality of culture – as a product-cum-process – is especially relevant here. Reddit, 4Chan and early message boards collated people with similar interests and relied on user engagement (Ritzers’ prosumers) to drive content creation and communication. As TikTok came to dominate the social media landscape, the introduction of highly personalised and algorithmically-driven ‘For You’ pages further fragmented online groups into smaller sub-divisions and echo chambers.

One of the so-called ‘fathers of the internet’ Vint Cerf gave a talk at the Computers, Freedom and Privacy (CFP) 1999 conference. The title of his talk proudly stated that “The Internet is for Everyone”. In a way, the fact that people can come together to create extremely-localised sub-communities is nothing short of fantastic. Despite pre-dating the internet as we know it (or even how it was in 1999), Deleuze and GuaIari were similarly understanding of the cultural power behind artistic difference: “In no way do we believe in a fine-arts system; we believe in very diverse problems whose solutions are found in heterogeneous arts.” (Deleuze and GuaIari, 1987: 343). Including brain rot in this assertion is surely pushing the boundaries. Yet there remains things to be learnt.

I should clarify, I don’t see brain rot in the same way that the Oxford Dictionary does. Brain rot, or more commonly brainrot, is, to me, an artistic genre; whilst it does slightly pain me to write that. I sympathise with the above definition: scrolling whatever social media platform for hours on end (doomscrolling) certainly can affect your mental state. This may not necessarily be a negative thing, being able to switch off after a long day has some benefit and has been explored as thus in various research papers. But by-and-large, its certainly a negative practice. However, to me, more truth lies in the secondary definition: “something characterized as likely to lead to [mental or intellectual] deterioration.“

There is plenty of poor quality media out there. Recent changes regarding the accessibility and starting costs to AI programs has significantly worsened the caliber of content readily available on the internet. This is evidently apparent on Kwebbelkop’s TikTok. When GTA V came out, he was a semi-respected YouTuber. Now his feed is clogged with meaningless AI generated content and ‘reaction’ videos. It is a genuinely depressing watch and gives serious validity to the ongonig ‘Dead Internet Theory‘. Kwebblekop goes one step further, using AI to generate his reactions and speech rather than recording anything himself. The fact he makes money off of this – presumably good money – is simply baffling. Such poor quality reaction content is regularly reviewed on JJJacksfilms, and I urge you to watch some of his videos to understand the social and enconomic damage which arises from content theft and AI generation. I specifically used the AI tools on WordPress to create this articles featured image, showing how easy it is to use them.

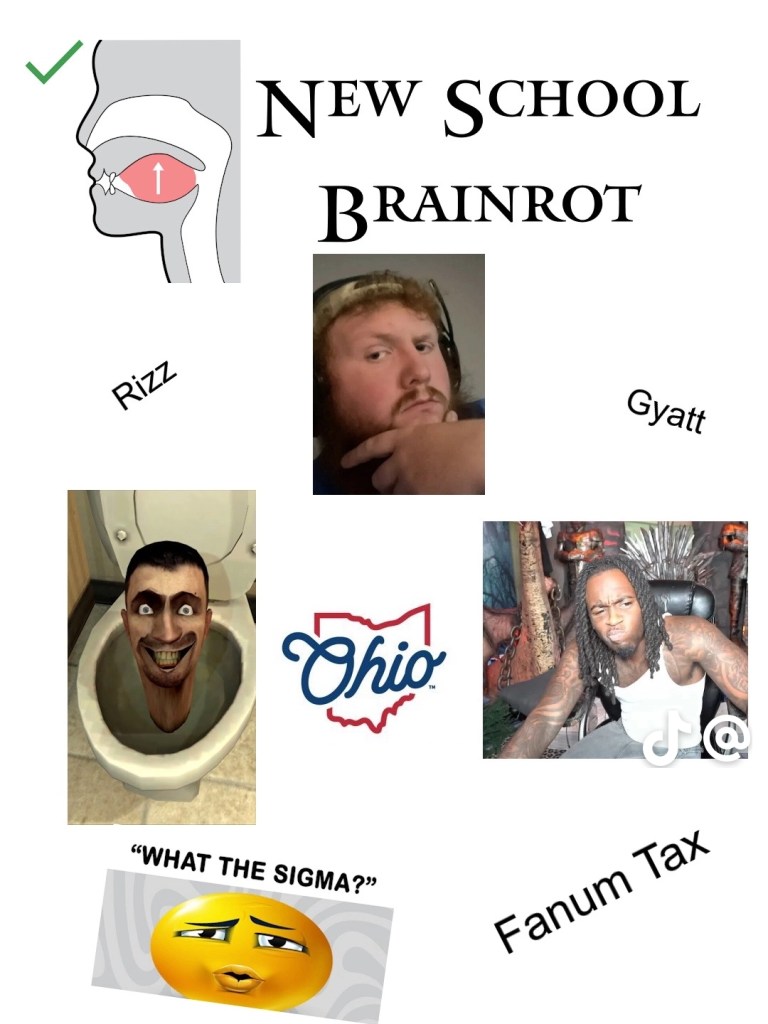

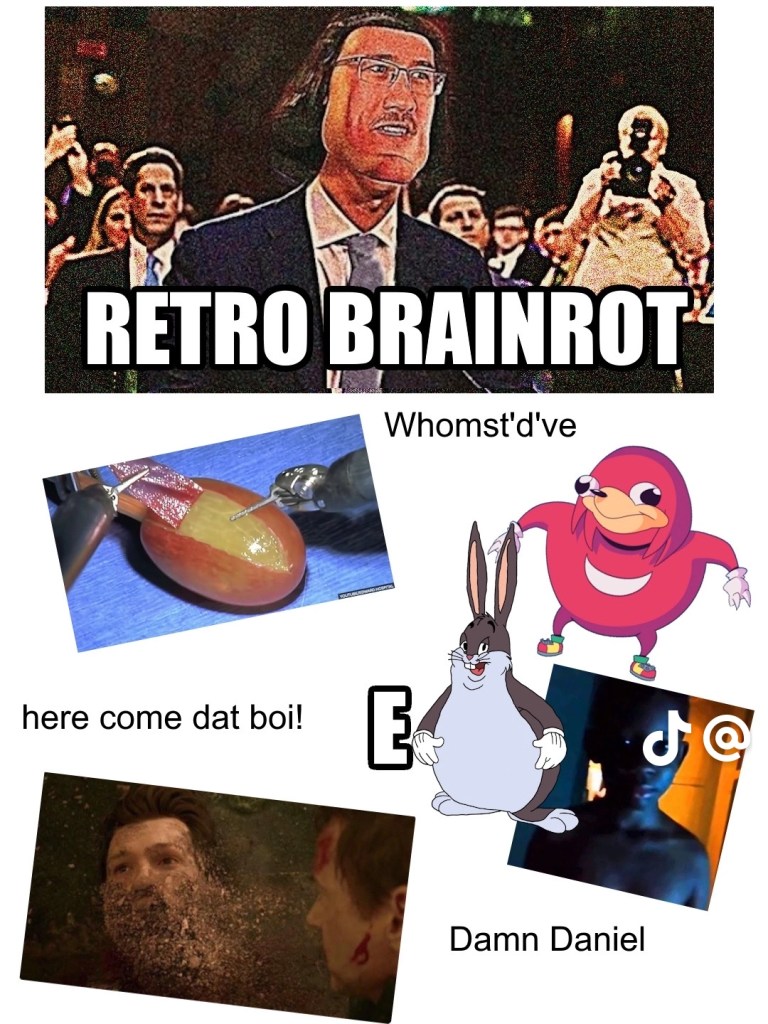

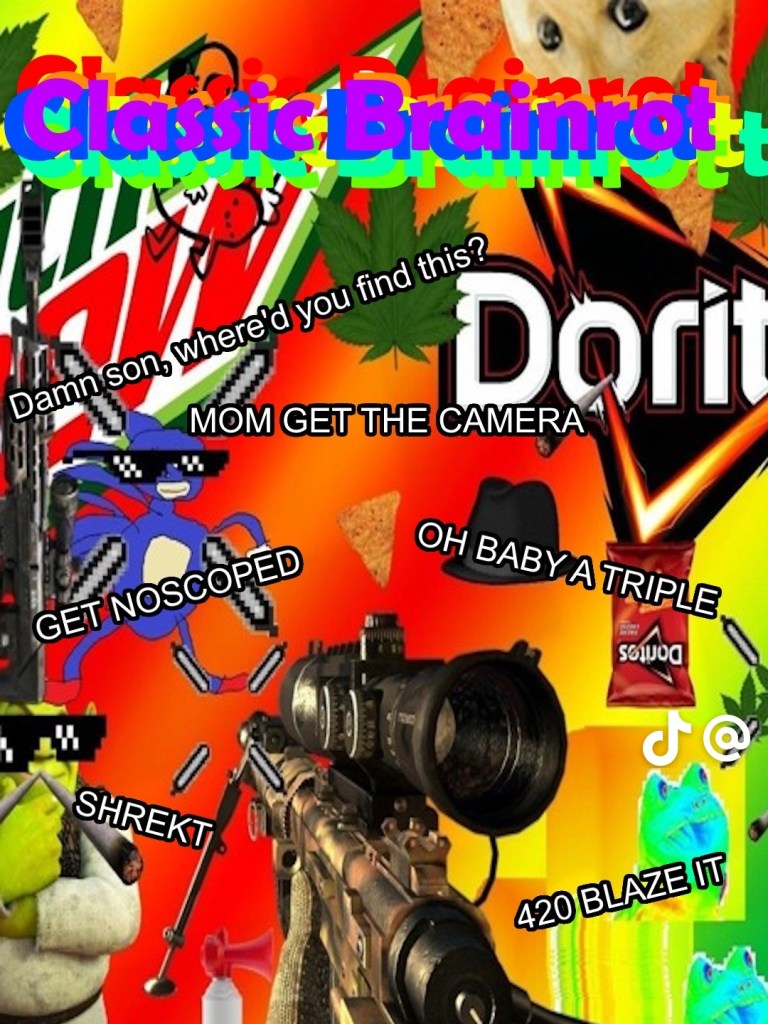

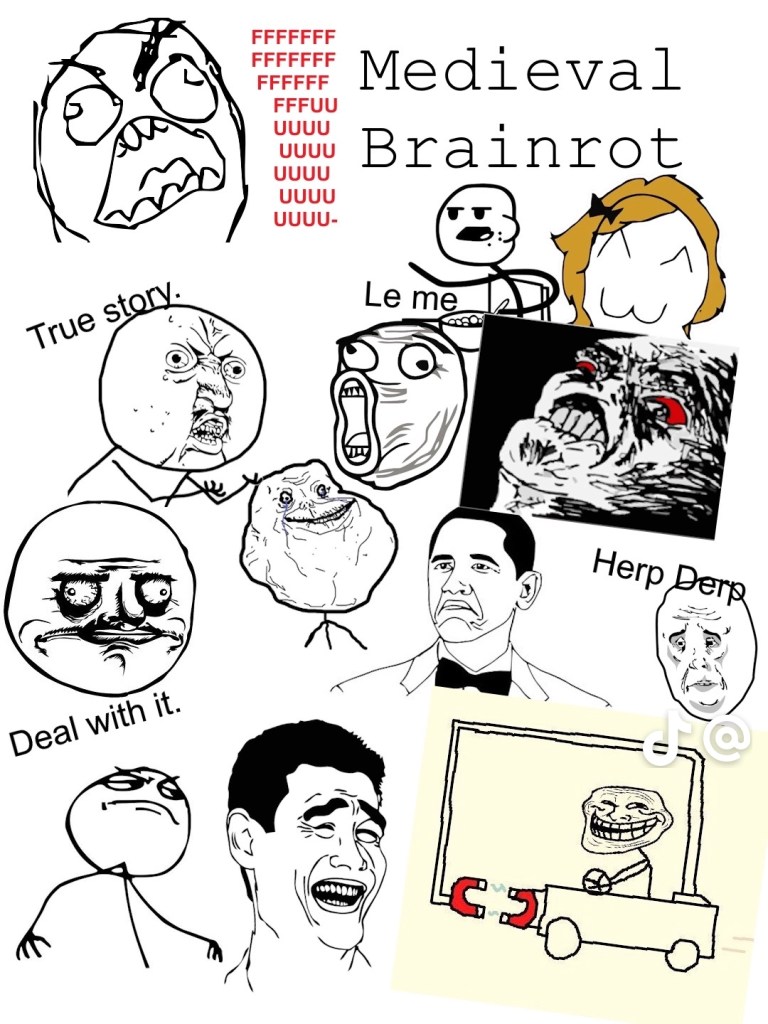

I do not contest that content such as Kwebbelkop’s is brain rot. But it is not how I understand and experience it. To some arguable degree, algorithmically-driven social media sites like TikTok curate a stream of content aligned to the users tastes. Mine is far removed from this, and I actively block or manage content to try and get a more interesting feed. I experience brain rot in a different way: a genre of culture which actively makes fun of the state of the internet and widespread popular culture. The slideshow below briefly works through some brainrot trends in recent internet history. Understanding and engaging with brainrot itself infers a certain internet nous, a deep understanding of sub-cultural trends and meme culture. Those around my age who were raised by the internet when there was less focus on screen-time, content blockers and – simply – less overall content probably recognise more references in the slideshow below than they should. Of course, the system of production is dynamic, and many of the memes referenced on the ‘New School Brainrot’ slide are already long forgotten, occupying small corners of the internet until they are ultimately lost to time. Whether such digitial content can be truly lost is a conversation for another time; although, it is certain that they will be far removed from the public zeigeist.

@Lorenyarose on TikTok. I am unsure if they are the original creator.

Being contrary has always illuded to some form of comedy. Brainrot typically takes memes which have crossed from the underground depths of the internet into popular culture, and meta-ironises them through repeated overuse and re-contextualisation. One of my first examples of this was the YouTube Poop series, which took popular video content – whether it be TV shows, movies or other online media – and re-edited them to produce new ‘comedic’ content. One of the more damaging cases of this was the various videos involving Michael Rosen, a childrens poet. Editing his spoken-word poems into luwd and often racist and/or sexist remarks has serious personal and professional impacts. That being said, anything uploaded on the internet seems to be free rein for other content creators to ‘creatively reinterpret’, with outdated and inaccurate copyright and ‘fair use’ laws even preventing such pervasive content from being taken down.

With the expansion of social media platforms and independent content creation tools, more and more of this content appeared on the internet. TikTok is rife with it right now. Often times, the videos directly mock trends which can broadly be classified as ‘popular’, repeating niche quotes and including video clips until they almost loose all meaning. Refering back to JJJacksfilms, his skit called ‘Amazing videos I defintely didn’t steal‘ exemplifies this perfectly. #corecore, #fiberopticcore/#fiberopticcablecore and #shitposting are usually good spots for finding content with similar Dada-esque qualities which, whether explicitly or implicitly, contributes to a wider internet movement which regects normal social norms through satirical, nonsensical media. Often, such videos have no actual intrinsic or artistic value. Whether that means we can interpret them as meaningless or a political commentary on popular culture is up for personal debate.

Amazingly, brainrot particularly interests me as it directly relates to a load of the broadly-cultural research which I do. Internet sub-cultures are exactly that: sub-cultures. What is funny to a niche group is classified as a good joke, meme or remark. When that joke, meme or remark crosses the imaginary and illusive threshold into popular media, it is almost immediately annexed. In part, this constant cycling of media contributes to a highly dynamic system, constantly in search of the next thing. Brainrot bucks this trend, seeking to regain power and control of media through ironistation and satorisation. Fundamentally, something being underground and sub-cultural gives some sense of coolness. Something within the broad spectrum of popular culture is rendered cringe.

Relating to my research, a similar process occurs in DnB. For many years, DnB was that cool underground genre which never got airtime on the radio. That certainly contributed to the community aesthetics and ideology; that underground aesthetic. DnB music in many ways is anti-pop: its fast, aggressive, divisive, performative… unique. When early house music started to gain traction within popular society, DnB fans were quick to critique the 4×4 pattern and simplistic sound design, whilst simultaneously espousing how the syncopated patterns and distorted bass sounds in DnB were far removed from the commercialised music industry.

That being said, DnB is a genre constantly going through cycles of commercialisation and popularisation. In both the 2010s and at the start of the pandemic, DnB music gained such significant popularity that the commerical music and radio industries took notice and started giving some songs air time. The anti-establishment ideology driving DnB production is important here, as the two popular periods of DnB coincide with a lack of government trust and public uncertainty: 2010’s saw the end of Labour’s 13-year term in parliament after the financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic led to significant distrust in the Tory government as well as the idea of ‘governance’ as a whole. Normally, the songs which crossed the line into popular cutlure were the more digestible and easily-accessible tunes which connected more with the uninitated person. In both cases, significant community backlash occured, with many members complaining about the sudden spike in popularity and wishing to retain the ‘old ways’ of the genre. Little regard is given to the economic growth experienced here, with other forms of socially-connected capital preferenced. Just as many other communities create brainrot content mocking such popularity, DnB content creators similarly engage with such practices. You can check out my own here.

Various interesting questions arise form this process, particuarly regarding the nebulous masspersonal understanding of what constitutes ‘popular culture’. Where does that line lie? Who determines this? Although certainly a niche internet phenomenon, brainrot and its associated practices encourage us to stop and question the impact popular culture and overall commericalisation has on sub-cultural communities. In an age where you can go viral overnight through ubiquitous internet access and algorithmically-driven feeds, sub-cultures as an idea are constantly in question. I fundamentally argue here that brainrot content is a form of protest against this.

Leave a comment